Sing. Die. Repeat: The Story of Opera at the Portsmouth Music Hall

From Dennis Neil Kleinman, host of The Opera Connection

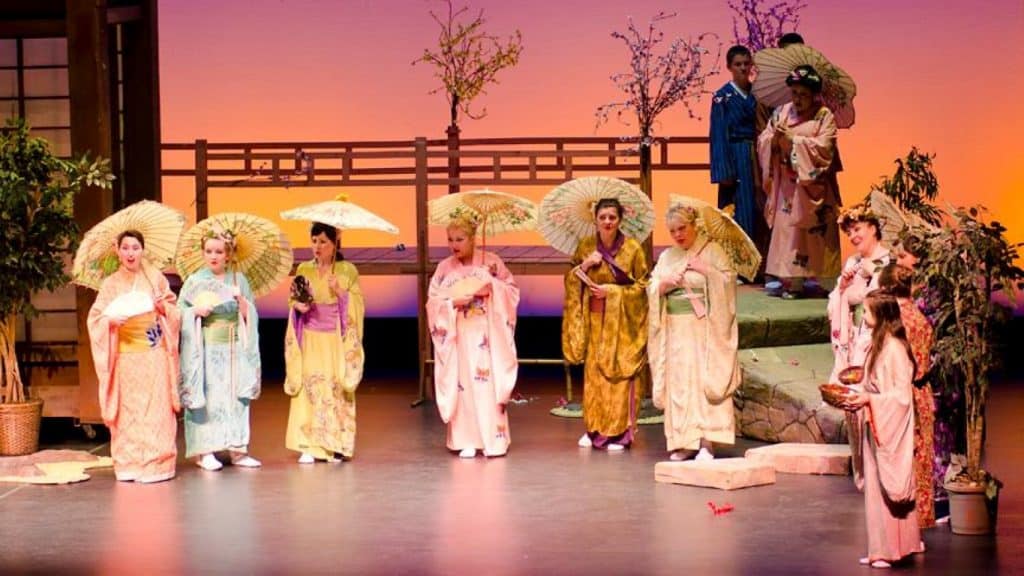

On Saturday, November 8, 2023, live opera will once again command the stage of the Portsmouth Music Hall with a performance of Puccini’s Madama Butterfly by Teatro Lirico d’Europa. This is an exciting and unexpected development for Seacoast opera lovers like me. I did a bit of research and learned that live opera has not had a place in the Music Hall’s line-up since 2006. I also learned about the long, often fraught relationship the Music Hall has had with this most dramatic and logistically challenging of art forms. What follows are some of the highlights of my research.

Generally speaking, opera has never been the entertainment choice for the vast majority of Americans. As Daniel Snowman put it in his book The Gilded Stage:

“Opera was widely regarded as the most elite of all the arts, originating as the entertainment of dukes and princes and involving European artists singing in Italian or German, portraying emblematic characters expressing extravagant emotions in dramatically implausible situations.”

He goes on to make the point that the very origins of the United States lay in the deliberate overthrow of old fashioned hierarchical European values in which all men were decidedly not created equal. If opera was going to make it in the States, it would have to fight to be heard over the rising tide of democratic, home-grown entertainment.

If it failed, that’s showbiz.

THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

Portsmouth provides us with an excellent example of this. When the Music Hall first opened its doors in January, 1878, Portsmouth was, to quote Dennis Robinson from his excellent book Music Hall – How a City Built a Theater and a Theater Shaped a City: “…a tough military seaport, known for its rowdy bars and alluring prostitutes.” Not surprisingly, the Music Hall’s roster leaned heavily on acts with low-brow content but high ticket sales like Buffalo Bill Cody’s troupe of stunt-riders and sharpshooters, P.T. Barnum’s freak show extravaganzas, melodramas, political satires, minstrel shows and magicians. Up against such crowd-pleasing competition, there was a good chance that opera wouldn’t survive at the Music Hall.

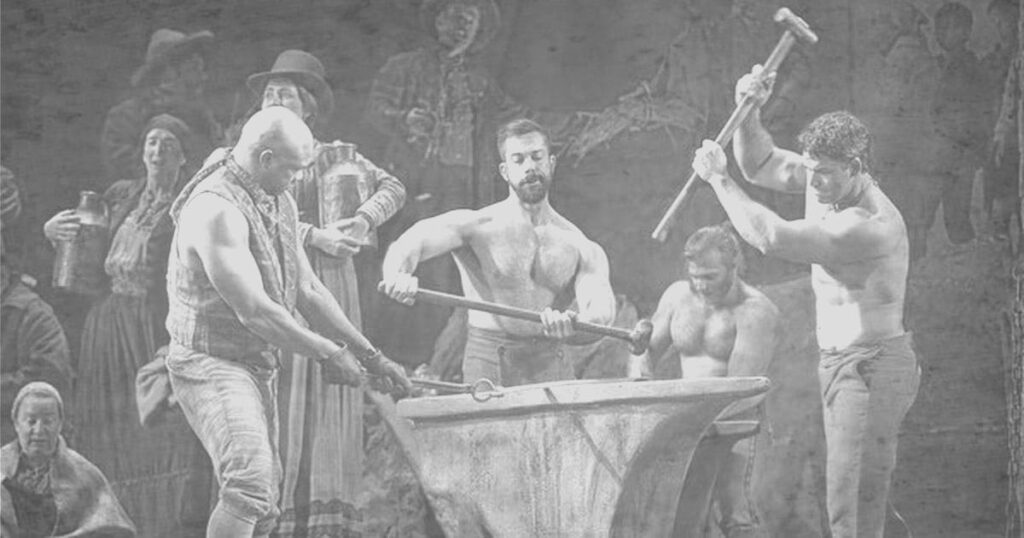

Surprisingly, it did. According to my tally, more than forty opera productions found their way to the Music Hall stage in the first two decades of its existence. Not surprisingly, most of them were not from the upper reaches of the quality opera spectrum. Only three ever found their way to the exalted floorboards of the Metropolitan Opera: Guiseppi Verdi’s bloody, brawny Il Trovatore, Friedrich Von Flotow’s light-hearted Martha, and Danial Auber’s broadly comical Fra Diavolo, one of the most popular operas of the 19th century though it is rarely staged today. (There is, however, a movie version from the 1930’s which features Laurel & Hardy!) Most of the rest were written specifically to tickle the fancy of the American audiences of their day and have fallen so far out of favor that even Wikipedia barely makes mention of them.

Most, but not all. The great exceptions, and by far the most performed operatic works at the Music Hall during this period, were the enormously popular light operas of Gilbert & Sullivan. Of the forty or so evenings of opera at the Music Hall between 1878 and 1898, a full 25 featured G & S works like The Mikado, The Pirates of Penzance, and Trial by Jury. Their smash hit H.M.S Pinafore alone accounted for 13 of those performances.

So opera found a place for itself at the Music Hall. But only the most broadly entertaining and accessible (read “unchallenging”) works needed apply. No Don Giovanni. No Tristan and Isolde. No Carmen.

THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

By 1900, America’s preferences in how to spend their time in the theater were changing. Vaudeville was coming into its own, and a whole new kind of entertainment experience, the movies, started to crowd out older, less exciting offerings.

Opera, expensive to stage and less of a draw than a new vaudeville joke-and-song-fest or Hollywood’s latest blockbuster, remained a part of the Music Hall’s mix, but just barely. Still, there were bright spots. On December 2, 1902, Pietro Mascagni, composer of the verismo masterpiece Cavalleria Rusticana appeared at the Music Hall in a production entitled Mascagni and his Italian Grand Opera Company. There is no way to know what was performed or how many of the citizens of Portsmouth were in attendance. But just the fact that a major opera composer of the day was invited to perform at the Music Hall indicates that there was an audience for quality opera fare.

But bright spots or no, opera continued slipping down the list of preferred Music Hall offerings. By 1911, there was exactly one night of opera, Verdi’s “Il Trovatore” compared to 60 nights devoted to vaudeville, movies, or some combination of the two. In 1949, the only opera performance at the Music Hall was the one featured in the Marx Brothers movie “A Night At The Opera”.

But as was said once in an opera (please don’t ask which one): “It’s always darkest before the dawn”. In the 1980’s came what is now known as the Portsmouth Renaissance. Positive reviews of the city brought droves of tourists, many from Metropolitan centers like Boston and New York. Some liked what they saw and decided to stay, bringing a new level of sophistication to the once rough-and-tumble town. This included a love of (you guessed it) opera.

THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY

The Music Hall recognized the shift in tastes, and by the dawn of the Aughts, live opera was once again appearing regularly. And this time it wasn’t just Gilbert & Sullivan but the heavyweights of the operatic repertoire – Mozart, Verdi, Wagner, Puccini. The boom lasted until 2006 when the Met began broadcasting its own world-beating live performances into venues like the Historic Theater. Now, for a reasonable price and without having to travel hundreds of miles, citizens of Portsmouth were treated to the greatest singers in the world performing the greatest, most challenging works in the opera repertoire as well as daring works by living composers who pushed the boundaries of what opera can be.

Though the Met Broadcasts were almost unanimously appreciated by Portsmouth’s opera-loving community, their impact on live opera at the Music Hall was devastating. While one might say that live opera at the Music Hall was always on life support, it flatlined for the first time since the Music Hall first opened its doors in 1878. The final live opera performance at the Music Hall was, as far as I can tell, on April 4, 2006, when the Granite State Opera performed Madama Butterfly.

“LIVE” LIVES!

On November 8, 2023, live opera will live again, picking up where it left off with a performance of Madama Butterfly. How long will this new era last? How many great opera performances will we get to see performed live at the Music Hall in the coming years? There is no way to predict. But let me just say that staging operas is still an expensive, logistical nightmare, and opera will still have to compete against all of the excellent programming the Music Hall is currently bringing to Portsmouth.

That’s showbiz.